The Battle of Grahamstown

Our story starts in 1812 after Colonel John Graham had ruthlessly cleared the Xhosa out of the Zuurveld south of the Fish River. Following this, the small military garrison of Grahamstown was established.

Turmoil Among Proud Chiefs

But behind the scenes of failure, the proud Xhosa beaten by Graham were in turmoil which led to a mighty battle between the Rhahabe chiefs, Nqika and his uncle Ndlambe, at Amalinda.

As history writes, a prophet chief named Makana was able to unite the fragmented Xhosa, convincing them that their trouble was not with each other, but rather the fight was with the British occupation of the Zuurveld. Just 5 years after Graham’s brutal clearing, in April 1819, Makana assembled a combined force of around 10,000 Xhosa in the valley of the Fish River to the North of Grahamstown. Ok, this is where history gets spotty because that number might realistically have been around 3000!

Colonel Wilshire’s Fatal Oversight

On the 21st of April 1819, Colonel Thomas Wilshire, the commander of this small garrison of just over 300 men, was sent a message from Makana telling him that he should prepare himself as he, Makana, was coming to breakfast the next morning. Obviously, the Colonel did not understand what was on his horizon and ignored the warning. So, the following morning, he rode out of the little village to inspect some remounts for the cavalry.

Crossing a wide open plain to the northeast of the village Colonel Wilshire noticed around 3,000 (lets go with this number) Xhosa warriors streaming over Botha’s Hill towards Grahamstown.

Two men were dispatched to warn the garrison and Wilshire attempted to hold back the Xhosa advance. They eventually retreated into the town where fewer than 100 men of the Royal African Corps had been left to defend what was the East Barracks (lying some 1,000 yards east of the settlement on the banks of the Kowie River).

Xhosa Warriors Decend on Grahamstown

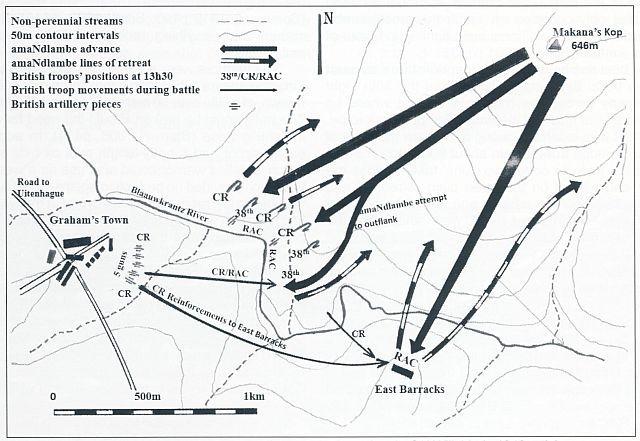

Map from the Military History Journal, Vol 18 No 3 – December 2018. The Battle of Graham’s Town 22 April 1819 By Pat Irwin.

A conjectural map of the battle,

based on Lt Col Willshire’s 1846 article.

Looking at the map you can work out where 45 men of the 38th Regiment of Foot, Colonel Wilshire’s regiment, along with the remaining 70 odd men of the Royal African Corps and the 121 men of the Cape Regiment were all moved onto some high ground overlooking the valley down which Colonel Wilshire was retreating ahead of Makana.

As you can see, Makana instead of attacking directly spent some time rallying his men on the high slopes above and east of the village. This gave Colonel Wilshire the time needed to organize his defenses.

Wilshire’s Men Brace for Impact

As you can see, Makana instead of attacking directly spent some time rallying his men on the high slopes above and east of the village. This gave Colonel Wilshire the time needed to organize his defenses.

The men were moved closer to the east barracks where they were deployed overlooking a deep ditch looking up the slope towards where Makana was assembling. Five guns were deployed above and behind the troops to cover them and the approaches to the east barracks. On two occasions men were sent up towards the gathering Xhosa in an attempt to draw them into battle. Makana didn’t budge. As you can see, he divided his force into four divisions and at around noon Makana attacked.

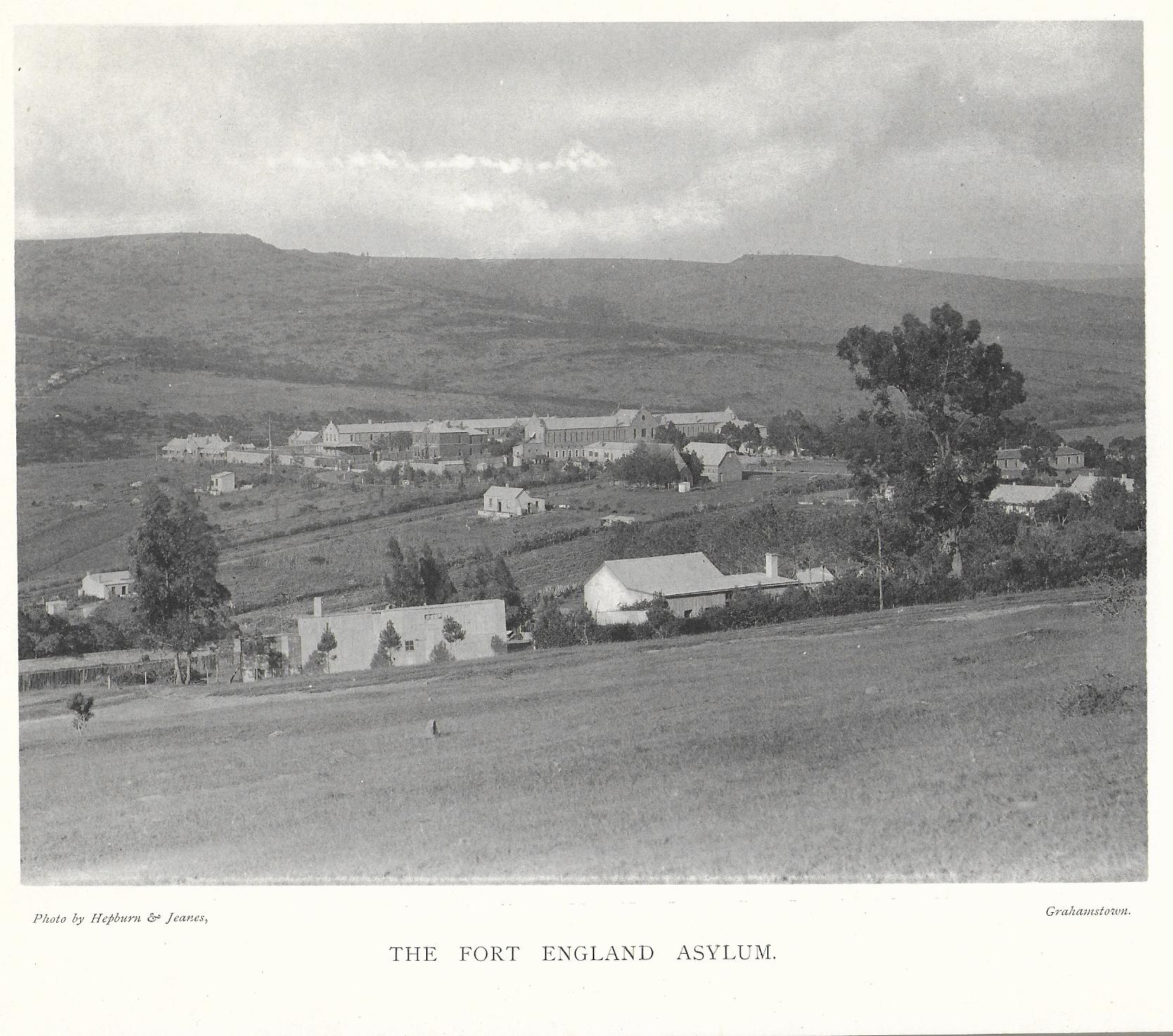

An early photo from a book called “Grocott & Sherry’s souvenir of Grahamstown” published in 1898, of Fort England Asylum, the site of the East Barracks during the attack on Grahamstown by Makana in 1819. The slope on the top left of the photo is where Makana gathered his men for the attack.

The Xhosa’s Relentless Advance

One division was sent south to cut off any retreat and two divisions under Mdushane and Ndlambe’s son and Kolbe of the Gqunukhwebe were dispatched to attack the troops formed up in front of the cannon. The rest, under Makana himself, attacked the east barracks. As soon as they were in range, Wilshire’s guns opened up, firing case shot into the densely packed ranks of the advancing Xhosa. Having never experienced cannon fire before, the warriors went to ground hesitating under their shields. But not be dissuaded easily, they continued to advance, crouching behind their shields until they were in musket range. Then they would charge the British line, and repeatedly be driven back by the guns and volley fire from the infantry’s muskets.

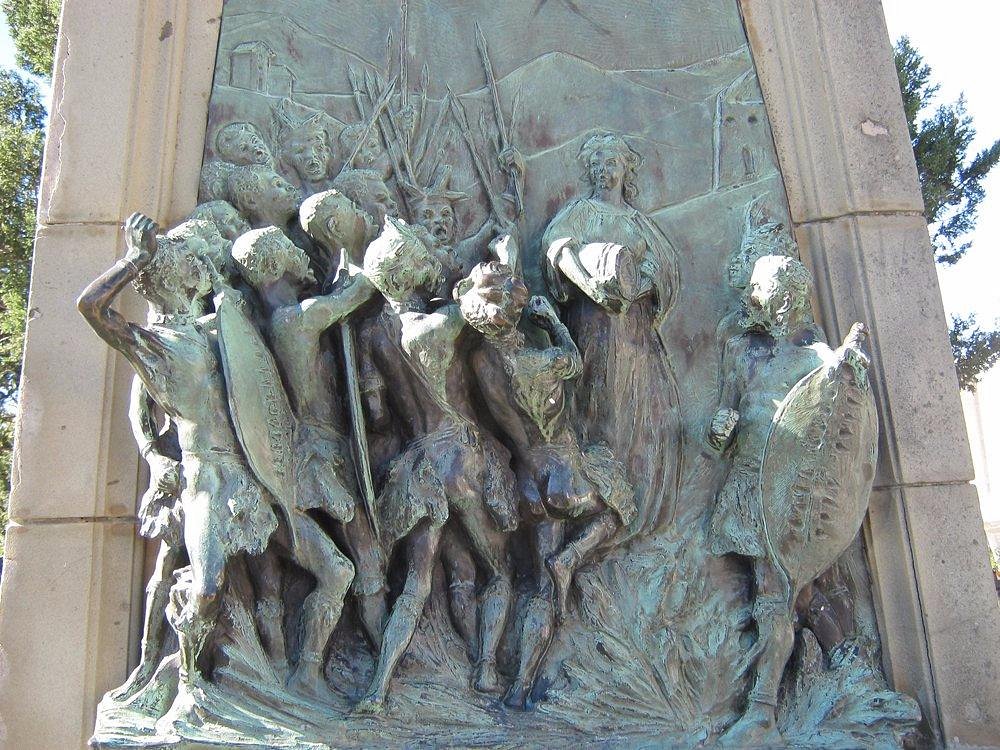

The Legend of Elizabeth Salt

But the proud Xhosa were not to be underestimated, Makana was able to breach the walls of the East Barracks and drive home his attack. While desperately firing out of the windows of the barracks, Lieutenant Cartwright and his men of the Royal African Corps were able to hold them off. Legend has it that at this point the defenders of the East Barracks were running low on powder. Seeing their plight, Elizabeth Salt, the wife of one of the barrack soldiers, wrapped a bag of gunpowder in a shawl and walked right through the attacking Xhosa, knowing that as a woman she wouldn’t be harmed. Notably, during 100 years of conflict, there is only one recorded account of a woman being killed by the Xhosa. Recorded where is the big question, as to date I have not been able to track down who this woman was.

Turning the Tide

Returning to our story, at this point, there is some speculation about the actual event, but it appears that 130 men under the Khoikhoi hunter Boesak came to the aid of the garrison. They had been patrolling the hills to the south and hearing the commotion Boesak led his men into the village, where he joined up with Wiltshire. These crack shots singled out the Xhosa chiefs and began to pick them off. The Xhosa attack began to waver. At first Mdushane and Kobe began to withdraw followed soon after by Makana from the East Barracks. By 3.30 that afternoon the Xhosa forces had begun fleeing back over the fish river, leaving nearly 1,000 dead on the battlefield. Remarkably, Wilshire’s losses amounted to three killed and five wounded. This all happened in a little under four hours.

The battle area on the slopes of the hill and the stream is still known as Egazini, Place of Blood. Colonel Wilshire was to remark two days after the battle that at one point he wouldn’t have given a feather for Grahamstown.

Makana gave himself up six months after the battle and became one of the first political prisoners imprisoned on Robben Island. He had come under criticism by many of the other Xhosa for starting the war. So he decided that if he was being blamed for starting it by giving himself up, that may stop the war. Makana tragically drowned the following year while attempting to escape. Perhaps he died not realizing how close he had come to beating the British, because in a twist on this tale, it is not actually known whether Boesak joined the battle. The original account by Wilshire doesn’t mention it. It is only mentioned in later accounts many years later.

The Untold Possibilities of Makana’s Victory

The battle area on the slopes of the hill and the stream is still known as Egazini, Place of Blood. Colonel Wilshire was to remark two days after the battle that at one point he wouldn’t have given a feather for Grahamstown.

Makana gave himself up six months after the battle and became one of the first political prisoners imprisoned on Robben Island. He had come under criticism by many of the other Xhosa for starting the war. So he decided that if he was being blamed for starting it by giving himself up, that may stop the war. Makana tragically drowned the following year while attempting to escape. Perhaps he died not realizing how close he had come to beating the British, because in a twist on this tale, it is not actually known whether Boesak joined the battle. The original account by Wilshire doesn’t mention it. It is only mentioned in later accounts many years later.

One can only imagine what may have happened, how the landscape of our history might have been affected had Makana fought to victory. Especially considering that the next year, in 1820, over 4,000 British settlers arrived in Algoa Bay, and changed the land forever. A land that by then had already seen 40 years of conflict – and the most bitter was yet to come.

As far as I’m concerned This battle was pivotal to our history because at that time there was much debate as to whether it was worthwhile securing the eastern boundary of the colony due to the number of men needed to do that. Had Makana succeeded it may have changed the course of history with the boundary moved closer to Cape Town, around the Sundays River Valley.

Pat Erwin wrote his thoughts on what might have happened should things have gone differently in his paper “The Battle of Graham’s Town 22 April 1819” published by The South African Military History Society.

“To get some perspective on the scale of this event, we might note that it ranks low in the annals of British military history, receiving only seven lines in Fortescue’s definitive History of the British Army (Fortescue, 1923, p394). Some historians have dismissed it as no more than a major skirmish. In the South African context, however, the result had long-term consequences, not only for Britain’s recently acquired Cape Colony and the future of its eastern border region, but for the general westward migration of the isiXhosa-speaking clans. Had Makana and his amaNdlambe won the day, which they should have, it is possible that other clans may have joined them in a great sweep well beyond the village and fort at Algoa Bay as had occurred previously in the Third Frontier War. The semiitinerant Trekboers in the area may finally have abandoned the volatile frontier zone and the Great Trek might have taken place earlier than it did, with unknown consequences. In such an event the British authorities in the Cape Colony may have decided to reconquer the territory but might equally have decided to abandon it as an unnecessary expense with little or no return. Willshire (1846, p2) himself mentions the likely loss of the frontier under such circumstances. In either event, there would have been no British settlers arriving in the Eastern Cape in 1820, and the history of the area would have been entirely different. In terms of South African history, it was a decisive battle.”

In hindsight, it might have changed a lot, but that’s a chat for around the fire!