Bloodlines Across Divides

In recent months I have found myself drawn back into the threads of my own family history, and in doing so, I have come to appreciate with greater clarity how closely ordinary lives were entangled with the great events that shaped South Africa. What has struck me most is that within my own bloodline, men and women stood on opposite sides of the same conflict, bound by kinship yet separated by war, loyalty, and circumstance.

A Family Story from the Anglo Boer War

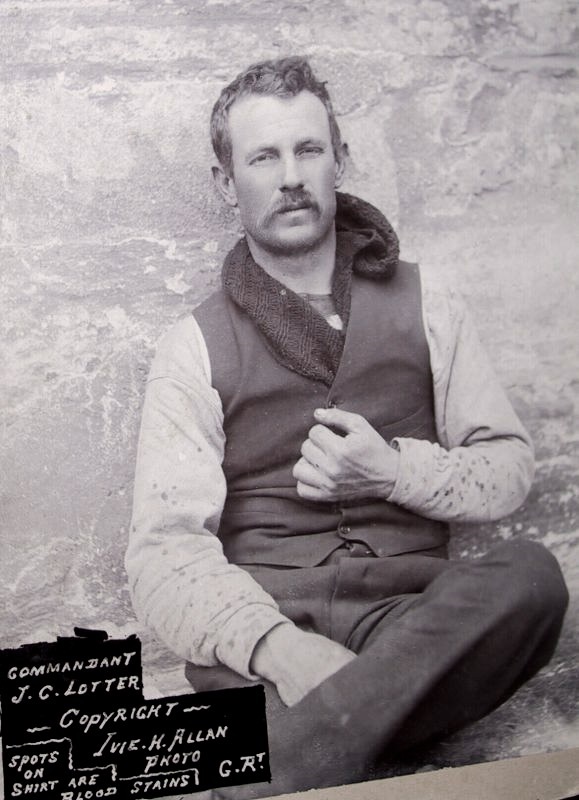

On my father’s side, my great grandmother was born a Lotter. She was the sister of the notorious Commandant Hans Lotter, a man whose name became synonymous with rebellion, defiance, and unflinching resistance during the Anglo Boer War. Lotter was one of the Cape rebels, Afrikaners who rose against British rule inside the Cape Colony itself. Where many Cape Dutch families chose caution, or neutrality, Lotter chose open defiance.

Hans Lotter’s commando operated in the eastern districts of the Cape, drawing men from farming families and rural communities who shared a sense of cultural loyalty to the Boer republics and a deep resentment of British authority. His operations were bold and provocative. He sabotaged railway lines, intercepted supply columns, and sought to destabilise British control of the countryside.

To the authorities he was a traitor. To many sympathetic farming communities he was a patriot. His eventual capture in September 1901 marked a turning point in the suppression of the Cape rebellion. He was tried by a British military court and executed by firing squad. In death, as in life, he remained a figure of controversy, embodying the fractured loyalties of a divided land.

Camdeboo whispers and the flogging of Frans Smit

The winter of 1901 settled cold and sharp over the Camdeboo, and with it came rumours that travelled faster than any mounted patrol. One rumour in particular reached Hans Lötter: a quiet farmer named Frans “Fransie” Smit had been seen talking a little too freely to a British column moving through the district.

Lötter did not shrug off rumours. Not in 1901. Not when British patrols were tightening their net and every water point, every koppie, every kraal could mean the difference between escape and capture.

So one afternoon, dust rising behind their horses, a handful of Lötter’s men rode up to Smit’s homestead. Chickens scattered. A dog barked once and fell silent. Smit, surprised and wary, was told to come with them.

He must have known what the talk was. Everyone knew the British had found a much-used spring in the veld a few days earlier. And everyone knew Lötter suspected someone had talked.

When Smit stood before him, Lötter was in no mood for careful deliberation. The commando had been hounded for weeks, sleep was thin, tempers were shorter, and trust was the rarest commodity on the frontier. In that tight, wind-bitten circle of mounted men, Lötter accused Smit of guiding the khakis to the water. Smit denied it. Perhaps he told the truth. Perhaps he bent it. Either way, Lötter believed none of it.

He ordered that Smit be tied to a wagon wheel.

There was no drama, no shouted threats. It happened with the grim efficiency of men who had done hard things before. The wheel creaked, the rope pulled tight, and the first lash cracked through the cold air. Some say there were a dozen strokes; others say many more. What they all agree on is that Smit could not stand properly for days afterward.

The story travelled far. The British brought it up during Lötter’s trial as proof that he punished civilians without mercy. Locals told it for years after the war because Smit’s family stayed on the land, and the marks left by that day never really faded.

In those retellings, the tale is less about cruelty and more about the fear Lötter inspired: he was bold, brave, admired by many. Yet he could turn flint-hard when he believed someone had put his men at risk. Even fellow Afrikaners were not spared when loyalty seemed to crack.

Yet within the same family line flowed a very different story

My great grandfather, William Henry Fergus, was a Scottish trained medical doctor who settled in Tarkastad in the Cape Colony. He was not a man of politics, but of practice and duty. In a district of scattered farms and long distances, he travelled by scotch cart and horseback across rough tracks to reach the sick and injured. His world was one of leather medical bags, glass medicine bottles, bandages, and handwritten notes, carefully carried with him from homestead to homestead.

This is the well-travelled, work-scarred medicine box that once belonged to my great-grandfather William, preserved exactly as he last packed it.

The old wooden chest sits open, its surface worn smooth by years of use. Inside, the upper compartment is crowded with small glass bottles in varying shapes and colours, most still sealed with cork stoppers and holding faint remnants of powders and tinctures. Some bottles cling to their original labels, browned and fragile with age. Below, a pull-out drawer holds larger glass bottles, spare corks, and a paper-wrapped box of medical supplies, all neatly divided into simple wooden compartments. The lid is lined with faded green felt, mottled by time, giving the whole box the unmistakable feel of a life once carried from farm to frontier, tending to the aches and emergencies of another age.

Lenient and conscientious, William established himself as a trusted figure in the community. Whether Boer farmer, English settler, labourer, or child, his duty was the same. Disease and injury did not ask where a man’s loyalty lay, and neither did he.

One morning, while returning from visiting patients in the district, he was stopped on a lonely stretch of road by members of General Smuts’s commando.

At that stage of the war, Smuts’s men had crossed into the Cape Colony during their bold invasion. They were exhausted, half starved, and dressed in ragged remnants of their former uniforms. Many had marched for weeks with little food and less rest.

They searched Fergus and took what they could use. His horse, his spare clothing, and items of equipment were confiscated. Even his boots were taken from him. Yet there remained, even in their desperation, a lingering respect for the function he served. These men understood that the district depended upon its doctor. To leave him entirely barefoot would have been to hinder his ability to return to his patients. And so, they handed his boots back to him.

In a gesture remarkable for its formality, they drew up and signed a written list of everything they had taken. They gave it to him with the advice that he should seek compensation from whoever emerged victorious at the end of the war. It was a small moment of humanity amid a brutal conflict, but it reveals much about the character of both the doctor and the desperate men who stood before him.

The threads of this story tighten even further through marriage

William Henry Fergus’s daughter later married the son of Dorothea Lotter, herself the sister of Hans Lotter. Thus, within one generation, the descendants of a Scottish doctor serving the colonial district were joined to the bloodline of a man executed as a Cape rebel. What had once been opposing forces in war were drawn together in peace, under the same family name.

This is the reality of South African history at its most intimate level. Our wars were not fought only by strangers. They were fought by cousins, neighbours, and, in time, by families who would later be joined by marriage and affection. The story of Hans Lotter and William Henry Fergus is not merely a tale of opposition. It is a mirror of a country itself, where loyalty, identity, and survival were never simple, and where, even after conflict, life found a way to weave divided strands into a single enduring fabric.

In reflecting on these two men, I am reminded that history is not only written in archives and textbooks. It is carried in blood, memory, and quiet family stories passed from one generation to the next. In my own lineage, the Anglo Boer War did not belong to one side or the other. It belonged to both. – Alan Weyer

Below is an image taken of the gathering for the death sentence pronouncement of Commandant Lötter at Middleburg

Lötter was captured in early September 1901, most commonly dated to 5 September 1901. His small commando was operating in the Cradock–Pearston area of the Eastern Cape when British and colonial troops (often with local guides) tracked them down and surrounded them in a place referred to in several accounts as Bouwershoek. After a brief engagement or encirclement, Lötter and most of his men were taken prisoner, with Lötter himself wounded during the action.

Images of Lotter and the gathering – Wiki | Image of medicine box – Alan Weyer