Walking with my Ancestors

My nephew Dayne has recently been delving into our family’s past, and what he uncovered has shifted the way I see our story in South Africa. Like many families, I believed our roots here were relatively recent. My paternal great-grandfather arrived from Germany in 1853 as a three-year-old boy and eventually made his home near Somerset East. My paternal grandmother was the daughter of a Scottish doctor who established his practice in Tarkastad in 1886. My mother was born in England, grew up in Kenya, and came to South Africa in the early 1950s, where she met my father.

That was the narrative I carried with me: German, Scottish, and English strands weaving together in the Eastern Cape. But further research uncovered deeper and far more complex ties, ties that reached back into the 17th century and carried with them the marks of conflict, colonisation, resilience, and survival.

One discovery was that my great-grandfather married Catharina Johanna Dorothea Lötter.

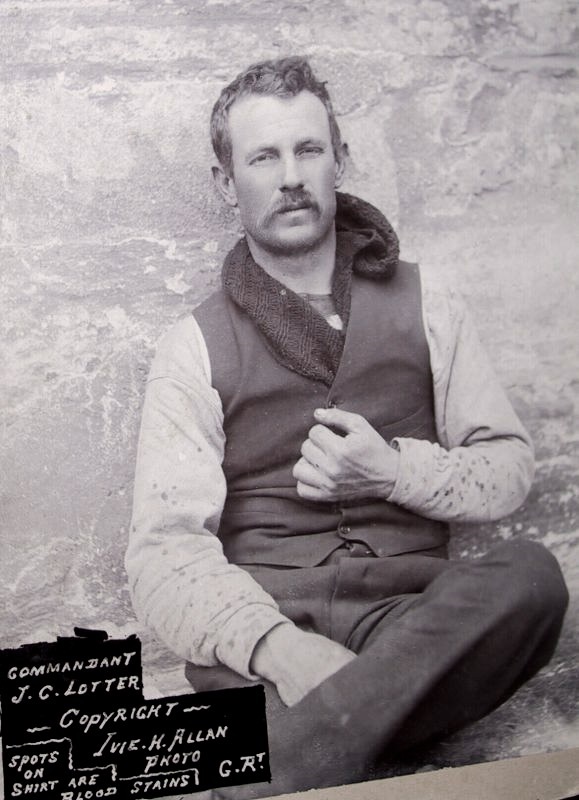

Her brother, pictured here, Johannes Cornelius Jacobus “Hans” Lötter, was executed by the British during the Anglo-Boer War as a Cape Rebel, a reminder that even within families, loyalties to empire and resistance could run in painful opposition.

“Hans” Lötter was a Boer commandant in the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902). His commando left its mark on the Cape Colony with sharp, unpredictable strikes that unsettled both Boers and British. Riding with Pieter Hendrik Kritzinger, he brought the war south in a way that was felt in towns, on farms, and along the railways. Tracks were torn up, lines of communication cut, and civilians were given stark warnings to stand with the Boer cause or face the consequences. His name carried both fear and fascination, and we will definitely be exploring him more in the future, as his story holds many tales whose impacts are still felt in our culture today.

When bloodlines divided history took sides

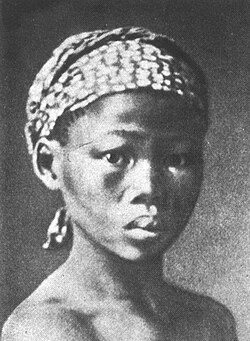

And then I discovered that the beautiful and famous Khoi lady Eva Krotoa, pictured below, was my 9th great-grandmother.

Through Catharina’s mother, a Buys, I learned of my ninth great-grandmother being Eva Krotoa. To find her name among my ancestors was extraordinary. Krotoa lived at the Cape in the mid-1600s, when Dutch settlement was still young and precarious. Taken into Jan van Riebeeck’s household as a twelve-year-old girl, she became a go-between at a time when two worlds, the Dutch newcomers and the Khoi people, were meeting in both fragile negotiation and violent collision.

She spoke Dutch and Portuguese, interpreted, and brokered peace. In 1662 she was baptised, and in 1664 she married Pieter van Meerhof, a Danish surgeon in Dutch service. This was the first recorded Christian marriage of a Khoi woman, a union that stood at the fraught crossroads of faith, power, and cultural assimilation.

Her life, however, was not one of unbroken honour. After her husband’s death she faced rejection and hardship, ultimately banished to Robben Island. She died young, at thirty-one, and was buried at the Castle of Good Hope. Yet her children, particularly her daughter Pieternella, carried her lineage forward. Today, her name is remembered as both a symbol of resilience and a witness to the first entanglements of African and European lives at the Cape.

The line also revealed the presence of three enslaved ancestors: two from Timor and one from Bengal. Their lives, recorded only in fragments, remind me that South Africa’s story is not just one of settlers and indigenous peoples, but also of men and women uprooted from distant shores and forced into new worlds.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Dutch East India Company brought enslaved people from across the Indian Ocean to the Cape. They carried languages, skills, and traditions, even as they endured bondage. To find them in my family tree is to acknowledge how deeply the history of displacement and survival is written into who we are.

These unions, between German and Scottish settlers, a Khoi woman and a European surgeon, enslaved people from Asia and African families, were not just personal choices or accidents of love. In their own time they were layered with power, struggle, and the fragile attempts of human beings to carve lives for themselves within systems far larger than they could control. And yet, they left descendants. They left me.

To look back across these centuries and see Krotoa, the executed Cape Rebel, the enslaved from Bengal and Timor, the German boy stepping ashore in 1853, the Scottish doctor arriving in Tarkastad, and finally my own mother travelling from England via Kenya to South Africa, is to see that history is not something abstract. It runs in our blood, shaped by suffering and survival, by courage and compromise.

– Alan Weyer

Images: Wiki