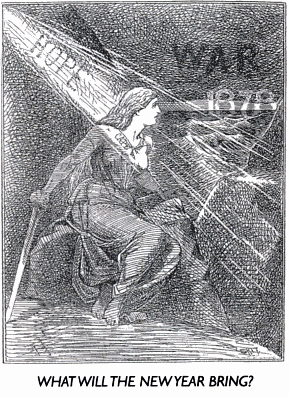

What Will the New Year Bring

That was the question on everyone’s minds as we rolled into 1878, especially in the Eastern Cape. And judging by this dramatic illustration, it seems no one knew for sure—though they certainly had their guesses! Looking back now, it’s safe to say that 1878 brought quite a bit.

For starters, the Ninth Cape Frontier War came to a close. After a hundred years of conflict between the British and the Xhosa, peace finally arrived in the Eastern Cape. It wasn’t an easy road to get there, though. The war left its mark on both sides, with lives lost, lands disrupted, and deep wounds to heal.

1878 wasn’t just about wars

But 1878 wasn’t just about wars. The colony was making strides in other areas too. This was the year telephones made their debut in the Cape, a mind-blowing technology at the time! And not long after that, telegraph lines connected Natal and the Transvaal, making communication across far distances quicker than ever. The world was getting smaller, and the Cape was on the cutting edge of this new communication era.

Still, while technology moved forward, politics got trickier. The debate over confederation was heating up, causing major tensions. The British government wasn’t too thrilled with how things were being run in the Cape, so they suspended the elected government and took control. A bold move that didn’t sit well with everyone.

As for the political cartoons, well, they captured the moment perfectly. Hugh Fisher, one of their best, sketched this exact piece. With ‘Hope’ lighting up the future, but ‘War’ casting a shadow, one can only imagine that it felt like anything could happen. And happen it did.

By the end of the year, the Eastern Cape was in a new chapter. The Frontier Wars were behind them, new technology was connecting people, and British control had never been stronger.

What a year, indeed.

.

After the end of the Ninth Frontier War, the British government took direct control of the Cape Colony’s frontier areas, suspending the local government and increasing military presence. The Lantern would have been deeply involved in reporting on these shifts, likely supporting the suspension of the Cape’s elected government in favour of stronger imperial control. For the conservative and pro-British readership of The Lantern, these moves were seen as necessary steps to ensure the security of the colony against what they perceived as an ongoing threat from indigenous resistance.

Founded by Alfred A. Geary in 1877, The Lantern arrived at a time of profound transformation and conflict in the Cape Colony.

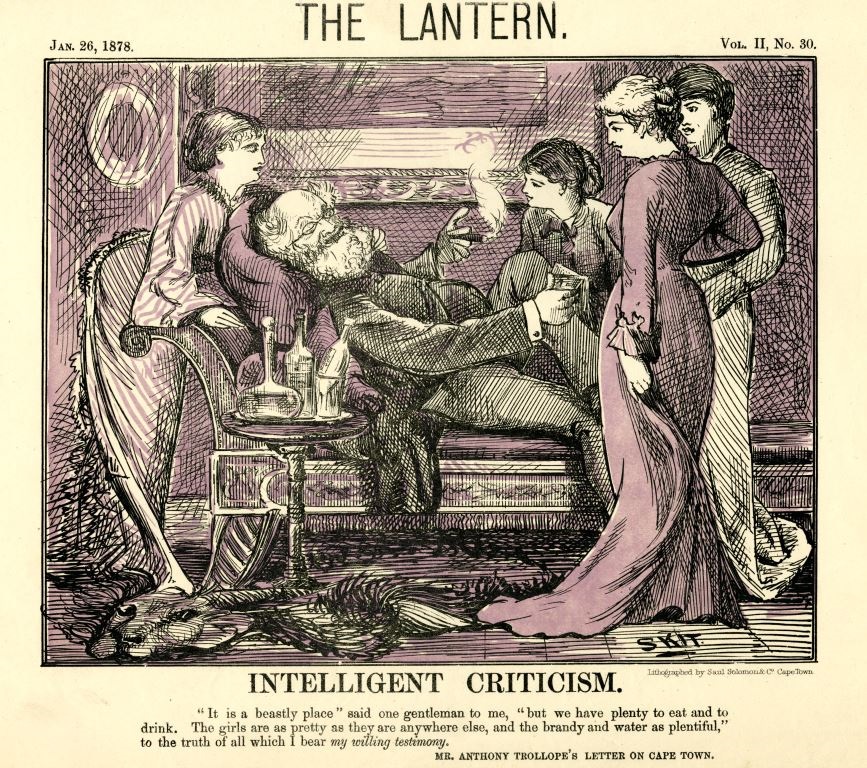

The Eastern Cape was a center of settler expansion, and The Lantern‘s pro-imperial stance reflected the desires of many settlers who saw themselves as agents of British civilization in what they viewed as a “savage frontier.” The 1870s and 1880s were a period where many colonial newspapers, like The Lantern, took firm stances on imperial issues such as the proposed confederation of southern African territories and the debate over the Cape Qualified Franchise, which allowed a limited number of non-whites to vote under certain conditions. The paper’s criticism of liberal politicians like Saul Solomon, who advocated for a more inclusive franchise, aligned it with the conservative, expansionist factions of the colony.

John Charles Molteno, the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, and his push for responsible government were hotly debated. The Lantern would have likely taken a hard stance against his more inclusive policies, favouring instead the stronger colonial control that culminated in the British-imposed confederation policies.

That all aside, by the mid-1880s, The Lantern began to suffer financially, mirroring some of the economic difficulties faced by the colony itself. Many smaller publications could not compete with larger newspapers like The Cape Argus and The Times. Thomas McCombie, who took over after Geary’s death in 1888 from illness, could not reverse the paper’s fortunes, and The Lantern eventually shut down. Debts rose and McCombie shut down the paper c. 1889 and moved to the Transvaal where he started a new paper the “Transvaal Truth”. However, he continued to face financial issues, including, to put it politely, an inability to meet his monetary engagements. After the Transvsaal Truth failed, he moved back to Cape Town where he eventually drowned in the Salt River.

By Hugh Fisher – Skit – The Cape Lantern, NLSA, Cape Town. Used under Creative Commons Licence.

The Lantern offers us an interesting window into the colonial mindset of Anglophone settlers in the late 19th-century Cape Colony. Its political cartoons, pro-imperial stance, and critique of liberal politicians make it a valuable historical source for understanding the attitudes and conflicts of the time.